-

QUALIFICATIONS

- For Linguists Worldwide

- For UK Public Services

- Preparation

- Policies & Regulation

-

MEMBERSHIP

- Join CIOL

- Professional Membership

- Affiliate Membership

- Chartered Linguist

- Already a member?

- Professional conduct

- Business & Corporate Partners

-

LANGUAGE ASSESSMENTS

- English

- All Other Languages

-

EVENTS & CPD

- Webinars & Events

- CIOL Conferences

- Networks

- CIOL Mentoring

-

NEWS & VOICES

- News & Voices

- CIOL eNews

- CIOL Awards

- The Linguist Magazine

- Jobs & Ads

-

RESOURCES

- For Translators & Interpreters

- For Universities & Students

- Standards & Norms

- CIOL & AI

- All Party Parliamentary Group

- In the UK

- UK Public Services

- Find-a-Linguist

Arabic Literary Translation and The King James Bible

By Dr Eyhab Abdulrazak Bader Eddin

Clear yet majestic

The King James Bible of 1611 has profoundly influenced modern English. Commissioned by King James I of England, this translation of the Bible was meant to speak to people in clear yet majestic language.

It quickly became the definitive English Bible for centuries, and along the way it introduced countless phrases and turns of expression into everyday speech. These phrases, often filled with weight and gravity, have endured in literature, politics, and common parlance to this day.

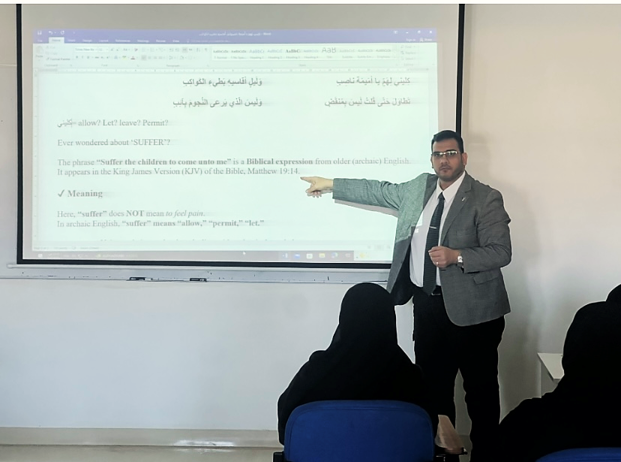

‘Suffer’ the children

In classrooms today, the King James Version (KJV) still surfaces unexpectedly. I vividly recall an incident when reading the words “suffer the little children to come unto me” with a class.

Many students were startled by “suffer,” thinking of it in terms of pain rather than its Old English meaning of “allow.” That moment in the classroom drove home to me how alive and yet oddly foreign these centuries-old words can feel to modern ears.

Because my course is fundamentally a translation course, I often pause with my students to compare KJV turns of phrase with classical Arabic constructions. We examine how both traditions rely on parallelism, rhythm and elevated diction, and students discover that the solemn tone they hear in the KJV has deep echoes in Qur’anic verses and Abbasid-era prose.

In class, I regularly guide students to place a KJV sentence beside a passage from classical Arabic literature – say, Al-Nabigha Al-Thubiani or EmreL Qais – to observe the shared reliance on balance, terseness and metaphor. This practice trains them to hear language not merely as meaning, but as cadence.

Imagery and cadence

As an instructor of a course titled Arabic Literature in English Translation, I often draw upon the KJV not only for its linguistic resonance but also for the way its imagery and cadence illuminate both English and Arabic styles. My own lexical choices and occasional archaisms – as when I consciously preserve older verb forms or paratactic phrasing – are deeply shaped by years spent reading and teaching the KJV.

Five verses in particular have shaped my teaching, especially when guiding students through tone, metaphor, register and ethical nuance in translation:

1. “In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth” (Genesis 1:1) - I use this verse to illustrate how solemn openings achieve grandeur through simplicity. Its rhythmic balance helps students understand how to translate elevated narrative beginnings into Arabic without over-embellishment.

2. “The Lord is my shepherd; I shall not want” (Psalm 23:1) - This verse allows me to show how metaphor travels across cultures. The image of the shepherd – protector, guide, caretaker – opens rich discussion about crafting metaphors in Arabic that preserve both tenderness and authority.

3. “Come unto me, all ye that labour and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest” (Matthew 11:28) - I frequently highlight this verse to demonstrate the interplay of compassion and rhythmic pairing (“labour” / “heavy laden”). Students learn how emotional register can be echoed delicately in Arabic prose.

4. “Let him that is without sin among you, let him first cast a stone” (John 8:7) - This becomes a model for ethical clarity in translation. We explore how conditional structures and moral admonitions can be rendered into Arabic in ways that remain rhetorically powerful.

5. “For now we see through a glass, darkly” (1 Corinthians 13:12) - I return to this verse when teaching ambiguity and metaphor. Its imagery of partial vision mirrors the translator’s own experience of working with mediated meaning, always reaching for clarity through a dim reflection.

A distinctive register

When the KJV translators met in 1604, they sought a style that would resonate with believers, and with the English-speaking world. Drawing on earlier Bible versions and original texts, they created a distinctive register of early modern English.

The translators balanced poetic flourish with straightforward narrative, resulting in a cadence which is both formal and memorable. Many sentences had a rhythm akin to Hebrew parallelism. The result was language that could seem ritualistic or ancient to new readers.

I find that reading KJV passages aloud often feels like reciting poetry or listening to a sermon. The tone can be grand and solemn, sometimes even stern, reflecting the translator's reverence for the text. This emotional register, that feeling of ritual or oration, carries through to modern readers and listeners – even if the exact meaning of some of the words is opaque.

Lingering phrases and idioms

Much of the KJV’s influence comes from phrases that survive into modern usage. Phrases like “the powers that be,” “signs of the times,” and “a thorn in the flesh” originate in biblical language.

Because the KJV was once read at home, in schools, and on radio, its expressions seeped into common parlance. We still say “my brother’s keeper” or call someone “a scapegoat” without knowing their origins.

In class, students enjoy discovering how some KJV idioms resemble moral maxims in classical Arabic, comparing for example, “my brother’s keeper” with ethical sayings from early Islamic and pre-Islamic traditions. These parallels help them recognise universal human concerns expressed through different but harmoniously elevated linguistic traditions.

I often reflect on how these phrases have become so naturalised that people use them without realising they came from an over four hundred year old Bible. Their survival owes to their poetic power and the force of repetition. A phrase like “cast the first stone” remains powerful because it is brief and vivid – and shocking – turning the visual metaphor into proverbial wisdom through countless repetitions over centuries.

Classroom encounters with archaic English

Not every KJV phrase fits neatly into modern speech. Words like “thou,” “thee,” “ye,” or verb endings like “-eth” can jar for contemporary readers. Many people reading the KJV today find such words quaint or confusing. Even common words like “wherefore” (meaning “why”) or “lest” (meaning “in case”) can cause a pause.

It is convenient to ask students to render archaic KJV pronouns into Arabic while maintaining the hierarchy or intimacy these forms once implied. This leads to rich discussions about how Arabic’s own pronoun system – singular, dual, plural; masculine, feminine – can carry shades of meaning that modern English no longer encodes.

I’ve noticed that listeners will often lean slightly forward when they hear an archaic term, perhaps drawn in by curiosity mixed with a hint of unease. We can almost feel the distance in time as we swap “you” for “thee.” Part of the emotional effect of KJV text is this sense of stepping into another era. The solemnity of an old-fashioned word can add emphasis or, paradoxically, make simple ideas feel more profound or even mysterious.

Waxing cold

In a literature class, I once quoted the KJV line “suffer it to wax cold” (from Revelations) and saw puzzled looks. Without context, “suffer”, again, seemed to mean to endure pain or accept something unfortunate. In reality it simply means “let it become cold.” That classroom scene, with eyebrows raised at the odd phrasing, was striking. It reminded me that language constantly evolves: what was everyday language in 1611 can feel like Shakespearean dialect today.

Such moments become opportunities to explore how both KJV English and classical Arabic preserve older verbs and idioms with metaphorical power. Students compare “wax cold” with Arabic expressions like “برد قلبه” or “خمدت نارُه,” noting how metaphor remains a bridge between eras and languages.

Students reacted with a mix of good humour and a little frustration! That laughter and confusion made the lesson all the more memorable: the sentence’s structure was clear once explained, but until then it sounded almost like a code. Moments like this highlight how the KJV’s old vocabulary can trip up readers – especially those for whom English is a second language – even if the underlying ideas are simple.

Tone and cultural resonance

Beyond specific words, the overall tone of the KJV leaves a strong impression. Its content can sweep from tranquility to thunderous judgment in a few lines. Poetry in the Psalms, prophetic warnings, or gospel parables all carry the translator's phrasing. The emotional register can range from tender (the image of an eye getting dim) to majestic (the heavens declaring glory).

In a classroom or church, someone reading a well-known KJV verse can evoke a hush or shiver of recognition. The KJV’s tonal beauty helps explain why it has been set to music and recited for generations.

Reactions to archaic KJV language today vary. Some readers relish the antique charm, enjoying the lyrical qualities as a connection to history. Others find it distant or puzzling.

But even without formal religion, the cadence of KJV phrasing often signals seriousness. It fascinates me how listeners seem to intuitively acknowledge the weight of an old turn-of-phrase, even if they can’t cite its origin.

Contemporary references

The KJV’s phrasing has seeped into literature, film, and public speech. Writers often weave biblical language into texts to lend gravitas, and filmmakers use its cadence for dramatic effect. I often notice how modern writers and speakers borrow KJV constructions to bolster a point. The literary and cultural power of KJV phrasing lies in its authority; using its style triggers a collective memory of solemnity and purpose.

In contemporary literature, Toni Morrison’s Beloved frequently echoes KJV cadences – its lamenting, prophetic tone mirrors biblical rhythms. I often read sections alongside passages from Isaiah or Jeremiah, helping students hear how parallelism and repetition move across centuries.

In film, the reflective voice-over of The Shawshank Redemption and the explicit biblical allusions in The Book of Eli offer concrete examples of how filmmakers rely on KJV diction to frame themes of judgment, hope, and deliverance.

In public speech, Martin Luther King Jr’s “I Have a Dream” speech – especially the section quoting “every valley shall be exalted” – remains a powerful demonstration of how KJV phrasing still shapes rhetorical power. I frequently share this with students to show how prophetic imagery survives in modern oratory.

Practically speaking, the KJV still appears at ceremonial occasions and in cultural life. In many English-speaking churches, passages are still read aloud from the King James translation. Wedding ceremonies, for instance, often feature verses from the KJV version, and famous literary quotes taught in schools may come from it. Even on social media, people sometimes write memes in a KJV-like style (“Thou shalt not scrolleth thine feed”), playing on its distinctive diction.

It is remarkable to recognise that a grammatical structure from 1611 can make a ‘selfie’ meme sound authoritative… I once saw a KJV-style caption on a smartphone meme and realised even satire can keep its instantly recognisable tone alive.

Enduring legacy

Reflecting on the KJV’s influence, one theme stands out: continuity through language. Despite centuries of change, many KJV phrases remain woven into how we speak. As an educator, I am often struck by how these antique words resonate with audiences today.

To me, this enduring relevance is more than just a quirk of linguistic history, it is a powerful testament to the emotional and aesthetic richness of English as shaped by centuries of literature.

The King James Bible, in preserving archaic structures and poetic cadences, doesn’t merely freeze a moment in time; it preserves the very human instinct to speak with beauty, solemnity and resonance. I often think of it not just as a religious document but as a literary cathedral: carefully built, intricately styled, and echoing with voices long gone, yet still familiar.

These exercises reinforce to my students that translation is not merely across languages but across eras. The KJV’s stately tones find natural companions in classical Arabic texts, and when students recognise these echoes, they gain a deeper awareness of how literary cultures converse across centuries.

The KJV continues to offer not only memorable phrasing, but also a spur to the human spirit through its powerful words of mercy, majesty, wrath and wonder that modern language all too often softens or loses. Perhaps that’s why I return to it, even in non-religious settings, to reawaken those deeper shades of linguistic meaning that stir both the intellect and the emotions.

Dr Eyhab Abdulrazak Bader Eddin is an accomplished Assistant Professor of Translation and Linguistics with over two decades of academic and professional experience across the Middle East. A member of CIOL, Chartered Linguist and MITI translator, he has held key roles at prestigious institutions such as Dhofar University, Kuwait University and King Khalid University. His research interests include translation theory, Quranic linguistics, and stylistics. Committed to educational innovation and community service, he continues to shape future translators and contribute to intercultural understanding.

Dr Eyhab Abdulrazak Bader Eddin is an accomplished Assistant Professor of Translation and Linguistics with over two decades of academic and professional experience across the Middle East. A member of CIOL, Chartered Linguist and MITI translator, he has held key roles at prestigious institutions such as Dhofar University, Kuwait University and King Khalid University. His research interests include translation theory, Quranic linguistics, and stylistics. Committed to educational innovation and community service, he continues to shape future translators and contribute to intercultural understanding.

You can contact Dr Bader Eddin on LinkedIn.

Views expressed on CIOL Voices are those of the writer and may not represent those of the wider membership or CIOL.

Filter by category

More

The Chartered Institute of Linguists (CIOL), Incorporated by Royal Charter, Registered in England and Wales Number RC 000808 and the IoL Educational Trust (IoLET), trading as CIOL Qualifications, Company limited by Guarantee, Registered in England and Wales Number 04297497 and Registered Charity Number 1090263. CIOL is a not-for-profit organisation.