-

QUALIFICATIONS

- For Linguists Worldwide

- For UK Public Services

- Preparation

- Policies & Regulation

-

MEMBERSHIP

- Join CIOL

- Professional Membership

- Affiliate Membership

- Chartered Linguist

- Already a member?

- Professional conduct

- Business & Corporate Partners

-

LANGUAGE ASSESSMENTS

- English

- All Other Languages

-

EVENTS & CPD

- Webinars & Events

- CIOL Conferences

- Networks

- CIOL Mentoring

-

NEWS & VOICES

- News & Voices

- CIOL eNews

- CIOL Awards

- The Linguist Magazine

- Jobs & Ads

-

RESOURCES

- For Translators & Interpreters

- For Universities & Students

- Standards & Norms

- CIOL & AI

- All Party Parliamentary Group

- In the UK

- UK Public Services

- Find-a-Linguist

The Linguist in Chinese - Showcasing translation skills #2

The Linguist Editorial Board member Professor Binhua Wang invited several MA translation master’s students in Chinese to translate one feature article from each of the four issues of The Linguist in the past year. Each translation has been translated by one, then revised by another, and then proof-read by their translation tutor.

Binhua’s initiative seeks not only to inspire these master’s students, but also to encourage other young linguists and perhaps their tutors, or indeed, other CIOL members to translate an article from The Linguist. Binhua’s hope is to inspire others to translate an article to promote translation skills, create opportunities for learning and to generate a wider readership for the excellent writing in The Linguist, as well as greater impact for CIOL more generally.

This is the second article in this series of articles from The Linguist to be translated into Chinese.

博物馆如何更 “吸睛”?

Engaging visitors

Meeting the needs of museum audiences requires a creative approach, argues Robert Neather

倪若诚 (Robert Neather) 认为,应采取创造性方式满足博物馆参观者的需求。

Translators:杨吟卓,徐璇,付添爵(南昌大学)Xuan Xu, Hanfei Xu, Tianjue Fu

Texts are an essential part of almost any museum exhibition. Whether it’s minimalistic object ID labels that give the title and barebones information, lengthy thematic panels or more ‘optional’ materials, such as leaflets and kids’ worksheets, texts provide much of the exhibition’s interpretive framework. Such texts raise a whole range of interlocking issues that influence translation strategy. These include the handling of specialist cultural terms, spatial restrictions on the amount of multilingual text that a label can accommodate, code preference (which language should be given prominence in a multilingual ensemble), and what other texts are available nearby in the exhibition space (the intertextual dimension).

文字材料是几乎所有博物馆展览不可或缺的组成部分。无论是仅提供展品名称及基础信息的极简标签、内容详尽的主题展板,还是宣传折页和儿童学习手册等“选择性”辅助材料,文字信息都构成了展览阐释框架的核心。这些文本内容涉及一系列问题,影响着翻译策略,包括专业文化术语的处理、多语标签的空间限制、语言优先性(在多语组合中确定主导语言)以及展览空间中邻近文本的互文性关联。

Balancing such factors can sometimes take considerable ingenuity. Yet it is when we consider audience engagement – how the text speaks to and interacts with the museum visitor – that the translator’s creative instincts are particularly important. For example, visitors from different cultures may have very different preferences as to how they wish to be addressed. Translators must consider what information is necessary or relevant – or, indeed, interesting – to a particular audience.

平衡这些要素往往需要极高的巧思。然而,正是当涉及到观者互动——即博物馆文本与参观者之间的交流互动时——译者的创造力才显得尤为重要。例如,来自不同文化背景的参观者对于自己如何被称呼可能存在截然不同的偏好。译者必须明确哪些信息对于特定受众而言是必要的、相关的,或者是具有趣味性的。

The question of engaging the visitor’s interest often involves what the art historian Michael Baxandall calls the “ostensive” or “pointing” function of language, where language is used to “locate the interest” of an artwork for the viewer.1 A text describing an artwork is not simply descriptive, he argues, but points to what is interesting. If a text refers to “a big dog” that is present in the artwork, “then ‘big’ is more a matter of my proposing a kind of interest to be found in the dog: it is interestingly big, I am suggesting.”2

吸引参观者兴趣的问题,通常涉及到艺术史家迈克尔·巴克森德尔 (1993 - 2008) 提出的语言“实指性”或“指示性”功能概念,也即通过语言为参观者“锚定”艺术品中值得关注的兴趣域。巴克森德尔认为,艺术作品的文本描述并非单纯描写记录,而是引导观者关注其独特价值。例如,倘若文本提及艺术作品中的“大狗”,“那么此处的形容词‘大’并非仅描述其体型,而是暗示这只狗的‘大’具有值得关注的趣味性。”

Translations often show adjustments that try to accommodate the potential for differences in viewer interest. In a leaflet text from the Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall in Taipei (pictured above), for example, a Chinese text describes the office of the former President in bald terms: 蔣中正總統坐姿蠟像由林健成先生塑造。 (‘President Chiang Chung-cheng’s seated wax figure was created by Mr Lin Chien-ch’eng.’) In the published English translation, however, we find: ‘Visitors can also see an extremely lifelike wax sculpture of President Chiang Kai-shek by Lin Chien-cheng sitting behind his desk.’

译者通常需要对博物馆文本的翻译作出调整,从而适应不同参观者可能存在的兴趣差异。以台北中正纪念堂(中国台湾)的宣传册为例,其中文文本对蒋介石的办公室进行了直白的描述:“蒋中正总统坐姿蜡像,由林建成先生塑造”。但是,在出版的英文文本中,我们发现相应的描述是:“参观者们还能看到,林建成先生建造的蒋中正总统蜡像坐在书桌前,极为栩栩如生。”

The subject of the sentence here is shifted explicitly to the visitor, with the verb ‘see’ added, drawing the viewer’s eye in to the sculpture. An exaggerative adjectival phrase, ‘extremely lifelike’, is inserted, and this is further reinforced by framing the statue as ‘sitting behind his desk’. In the context of the whole passage, not replicated here, it is also of note that this description is moved up much closer to the start of the text, giving it greater salience than in the Chinese. All this, combined with other similar strategies, seeks to inject greater interest into a tableau that might otherwise be somewhat dull for the non-Chinese visitor, and to direct the visitor to what is interesting in the scene.

在这句话中,主语明显转换为了参观者,再加上动词“看见”,将观者的目光引向了蜡像。此外,这句话还添加了带有夸张性描述的形容词短语“极为栩栩如生”,同时用“坐在书桌前”加以修饰,进一步展现了蜡像的“极为栩栩如生”。同时需要特别指出的是(此处未完整复现原文段落),相较于原版的中文文本,该描述在英文文本中被前置至开篇位置,更加开门见山,有利于突出描述性表达。此类策略的综合运用,旨在进一步吸引非中文背景观者兴趣——避免原本可能因文化隔阂导致的场景乏味——同时精准引导参观者关注场景中值得玩味的细节。

Working with playful texts

运用趣味性文本

The issue of creativity is particularly pronounced where the source text is itself written in a highly creative way. Consider, for example, the label ‘On the Waterfront’, describing Roman London’s port, from the Roman history section of the old Museum of London (when it was still in its London Wall incarnation). The creativity stems from a clear intertextual usage that is designed to create interest through a knowing or playful reference.

当源文本本身具有高度创造性时,如何进行创造性翻译这一问题便尤为显著。试想一下,以旧伦敦博物馆(原址位于伦敦城墙内)罗马历史展区的标签“码头风云”(‘On the Waterfront’)为例,该标签旨在描述古罗马时期的伦敦港口。其创造性翻译明显源于互文性策略,这种策略意在通过具有文化指涉性或趣味性的引用激发观者兴趣。

This is also seen in many other labels in the series (e.g. ‘All Along the Watchtower’, describing Roman lookout posts, and ‘All Roads Lead to… London’, on a label about transport links). In the case of ‘On the Waterfront’, we have an obvious allusion to the Marlon Brando movie of the same name, which presents the translator with several options. One might be simply to try and replicate the reference to the movie by using the established foreign language title. This might work in French (Sur les quais; ‘On the docks’), but it wouldn’t in German (Die Faust im Nacken; ‘The fist in the neck’).

此类互文性策略亦见于该系列其它标签,例如描述古罗马瞭望哨的标签“瞭望塔沿线” (‘All Along the Watchtower’) 以及展示交通路线的“条条大路通……伦敦” (‘All Roads Lead to…London’)。以“码头风云” (‘On the Waterfront’) 为例,其明确引用了马龙·白兰度 (Marlon Brando) 同名电影标题,这为译者提供了多种翻译选择。其一为直接沿用目标语言中既定的电影译名,以复现互文关联——但这一策略可能在法语标题 Sur les quais;‘On the docks’(“码头风云”)中尚可适用,在德语标题 Die Faust im Nacken; ‘The fist in the neck’ (“颈后重拳”)中则不适用。

A second solution could be to use a different popular reference from the target culture, which would retain the same kind of creativity but widen the choices available. Still another possibility could be to abandon any attempt at intertextual usage and employ a compensation strategy to introduce creative elements of another kind – for instance rhyme, rhythm or alliteration.

其二,译者可选取目标语文化中广为人知的独特参照,在保留源文本创造性的同时拓展可选策略。此外,译者亦可彻底摒弃互文性尝试,转而采用补偿策略引入其他类型的创意元素,例如韵律结构、节奏范式或头韵修辞等。

We should also consider the possibility of abandoning the creativity completely: some cultures may not see such playfulness as desirable or even appropriate in the context of a museum label presenting elements of the nation’s history. It is worth remembering also that intertextuality is often in the eye of the beholder – while the Brando reference might seem obvious, it might only be so to some viewers, perhaps of a certain age range.

除此之外,我们还需考虑彻底摒弃创造性翻译的可能性:在涉及国家历史叙事的博物馆标签中,某些文化可能认为此类趣味性表达既非必要,亦不合时宜。必须指出的是,互文性本质上具有受众主观性特征——尽管白兰度电影的标题引用具有明显的互文性关联,但这种关联可能仅针对部分观众,又或是特定年龄层群体。

Catering to the Kids

以儿童兴趣为导向

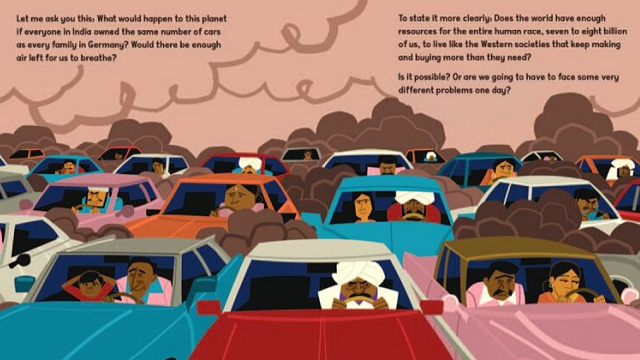

Creativity in the context of exhibition worksheets is an important element in engaging younger audiences. The following Chinese-English translation from a Hong Kong museum provides a striking example of how creative usage can itself be creatively handled. The text is from a worksheet page that encourages children to examine the colours of Chinese blue-and-white porcelain (pictured left). The title and first two sentences read: 青出於藍。青花 瓷器上的花紋, 是綠色的嗎? 可不是呢! 是藍 色的。(‘Blue comes out of indigo. Are the patterns on the blue-and-white porcelain vessels green? Absolutely not! They’re blue.’) However, in English, the text was rendered as: ‘Out of the Blue. Have you heard of underglaze blue porcelain or blue and white porcelain? They’re actually the same!’

Creativity in the context of exhibition worksheets is an important element in engaging younger audiences. The following Chinese-English translation from a Hong Kong museum provides a striking example of how creative usage can itself be creatively handled. The text is from a worksheet page that encourages children to examine the colours of Chinese blue-and-white porcelain (pictured left). The title and first two sentences read: 青出於藍。青花 瓷器上的花紋, 是綠色的嗎? 可不是呢! 是藍 色的。(‘Blue comes out of indigo. Are the patterns on the blue-and-white porcelain vessels green? Absolutely not! They’re blue.’) However, in English, the text was rendered as: ‘Out of the Blue. Have you heard of underglaze blue porcelain or blue and white porcelain? They’re actually the same!’

博物馆展览学习手册的创造性翻译,是吸引儿童参观的重要因素。以下是香港一家博物馆的汉英翻译实例,这个例子极为鲜明地展示了如何用创造性手法重构源文本的创意内核。案例文本选自该博物馆的学习手册,旨在鼓励儿童观察中国青花瓷的釉色特征。文本的标题与开篇两句原文为:“青出于蓝。青花瓷器上的花纹,是绿色的吗?可不是呢!是蓝色的。”然而,其英文译文为:“Out of the Blue. Have you heard of underglaze blue porcelain or blue and white porcelain? They’re actually the same!”(中文意思:“出乎意料。你听说过青花瓷或青花瓷器吗?它们实际上是一回事!”)

The Chinese title, Qing chu yu lan (‘Blue comes out of indigo’), is a four-character idiom which more metaphorically means ‘the student surpasses the teacher’. Here, however, this meaning is absent: the idiom is used simply as a playful way of referring to the blue theme of the porcelain. Neither a translation of the metaphorical meaning nor of the surface meaning will work. Instead, the translator haschosen another equally recognisable set phrase from the target language: ‘Out of the blue’. The rendering is especially clever because it retains some sense of the source text’s ‘out of’ construction while managing to keep the phrasing short.

中文标题“青出于蓝” (Qing chu yu lan,字面义为“蓝色源自靛蓝”)是一个四字成语,其隐喻意义为“学生超越师长”。然而,在学习手册中,这个成语仅作为趣味性表达指向瓷器的蓝色主题,无需译出隐喻意义。在翻译其隐喻义或字面义均无法实现功能等效的情况下,译者转而从目标语言中选取了另一同样广为人知的固定短语:“Out of the Blue”(“出乎意料”)。此译法尤为精妙,既保留了源文本“出于” (out of) 的句法结构,又通过习语的简洁性规避了冗赘阐释。

The two short opening sentences also deserve comment as they again require creative handling. In our literal English reference translation, the question asking if the blue patterns are green, followed by the confirmation ‘Absolutely not! They’re blue’, might seem somewhat ridiculous. Yet in the Chinese, worksheet users are simply being asked to disambiguate the word qing, which here means blue, but which can also mean green or even dark or black. In English, a direct translation won’t work, because unlike Chinese, English lacks a hypernym that will cover all the colours implied by qing.

开篇两句的翻译策略亦值得深入探讨,因其同样需要进行创造性处理。在英文文本中,如果将中文问答“青花瓷器上的花纹,是绿色的吗?可不是呢!是蓝色的。”直译为英文,其逻辑结构可能在目标语境中显得悖谬。因为,在中文原文本中,这一问答意在引导学习手册使用者对“青”这一多义聚合词进行语义解歧——该词在此特指蓝色,但其语义辐射域可涵盖绿色、玄色乃至黑色。而英文缺乏如中文“青”般具备广泛色彩外延的上位词,所以直译方法并不可行。

The English translator has thus retained the question-and-answer format of the Chinese but used a different question that instead addresses the two different names for this kind of porcelain. Creative translation here avoids the eyeroll that a more literal rendering might induce in the worksheet’s young users.

因此,英文译者保留了中文原文本的问答形式,但通过提出另一不同的问题,转而聚焦于同类瓷器的两种不同命名方式。此处的创造性翻译策略有效规避了直译可能引发的年轻使用者认知失调。

These various examples of creative handling ultimately remind us that creativity is at the heart of much museum translation. Indeed, as the translator Judith Rosenthal has written, such translation is fundamentally “a creative act”.3

归根结底,上述多元化的创造性翻译案例表明,创造性始终是博物馆翻译实践的核心要义。诚如翻译学者朱迪斯·罗森塔尔(Judith Rosenthal)所论,此类翻译本质上是一种“创造性行为”。

For more on this subject, see Robert Neather’s new book Translating for Museums, Galleries and Heritage Sites, published by Routledge.

欲深入探究相关主题,可查阅倪若诚的新著《博物馆、美术馆和文物古迹翻译》(Translating for Museums, Galleries and Heritage Sites),该著作由劳特利奇(Routledge) 出版社出版。

Notes

1 Baxandall, M (1985) Patterns of Intention: On the historical explanation of pictures, New Haven and London, Yale University Press

2 Ibid, 9

3 Rosenthal, J (2021) ‘Behind the Scenes – A career as an art translator’. In Ahrens, B, KreinKühle, M and Wienen, U, Translation – Kunstkommunikation – Museum / Translation – Art Communication – Museum, Berlin, Frank & Timme, 179-198

Robert Neather is Associate Professor and Department Chair in the Department of Translation, Interpreting and Intercultural Studies at Hong Kong Baptist University. He has published and taught extensively on museum translation. He is also a UN-qualified translator and has significant freelance translation experience.

Robert Neather is Associate Professor and Department Chair in the Department of Translation, Interpreting and Intercultural Studies at Hong Kong Baptist University. He has published and taught extensively on museum translation. He is also a UN-qualified translator and has significant freelance translation experience.

倪若诚是香港浸会大学翻译、口译和跨文化研究系副教授兼系主任。他发表了大量关于博物馆翻译的文章并从事相关教学。他还是一名联合国认可的译者,拥有丰富的自由翻译经验。

This article is reproduced from the Winter 2024 issue of The Linguist.

Read the article in Chinese here.

You can also read the first article in this series translated into Chinese 'Embrace the machine' here.

More

The Chartered Institute of Linguists (CIOL), Incorporated by Royal Charter, Registered in England and Wales Number RC 000808 and the IoL Educational Trust (IoLET), trading as CIOL Qualifications, Company limited by Guarantee, Registered in England and Wales Number 04297497 and Registered Charity Number 1090263. CIOL is a not-for-profit organisation.