-

QUALIFICATIONS

- For Linguists Worldwide

- For UK Public Services

- Preparation

- Policies & Regulation

-

MEMBERSHIP

- Join CIOL

- Professional Membership

- Affiliate Membership

- Chartered Linguist

- Already a member?

- Professional conduct

- Business & Corporate Partners

-

LANGUAGE ASSESSMENTS

- English

- All Other Languages

-

CPD & EVENTS

- Webinars & Events

- CIOL Conferences

- Networks

- CIOL Mentoring

-

NEWS & VOICES

- News & Voices

- CIOL eNews

- CIOL Awards

- The Linguist Magazine

- Jobs & Ads

-

RESOURCES

- For Translators & Interpreters

- For Universities & Students

- Standards & Norms

- CIOL & AI

- All Party Parliamentary Group

- In the UK

- UK Public Services

- Find-a-Linguist

The Linguist in Chinese - Showcasing translation skills 3

The Linguist Editorial Board member Professor Binhua Wang invited several MA translation master’s students in Chinese to translate one feature article from each of the four issues of The Linguist in the past year. Each translation has been translated by one, then revised by another, and then proof-read by their translation tutor.

Binhua’s initiative seeks not only to inspire these master’s students, but also to encourage other young linguists and perhaps their tutors, or indeed, other CIOL members to translate an article from The Linguist. Binhua’s hope is to inspire others to translate an article to promote translation skills, create opportunities for learning and to generate a wider readership for the excellent writing in The Linguist, as well as greater impact for CIOL more generally.

This is the third article in this series of articles from The Linguist to be translated into Chinese.

Make it sing?

赋文以韵?

Gene Hsu considers approaches to song translation and proposes a comprehensive way to discuss the process

Gene Hsu 关于歌曲翻译方法的综合研究

Translators:杨吟卓,徐璇,付添爵(南昌大学)Xuan Xu, Hanfei Xu, Tianjue Fu

In popular music, song translation is used to help the target audience understand the source song, but the translations are often not singable. Some are produced by translators or songwriters, while others are done by internet users. Although research in song translation is increasing, it is still rare. Most existing research discusses aspects of translation and rhyme, but few take music theory and songwriting into account.

在流行音乐领域中,歌曲翻译旨在帮助目标受众理解原曲,但翻译后的歌词常常难以直接演唱。一些歌曲翻译由专业译员或词曲作者完成,另一些则由网络用户进行。尽管关于歌曲翻译的研究逐渐增多,但仍属凤毛麟角。现有的研究大多数聚焦于翻译和韵律问题,而较少涉及乐理和词曲创作。

My study of interlingual song translation1 focuses on the roles that songwriting plays in song translation. I started by doing a review of the literature. Lucile Desblache proposes that there are three main forms in interlingual translation.2 The first is when “lyrics are provided to be read/heard independently from or in conjunction with the original song or musical text”. In the second, lyrics “are intended to be sung in another language than the original language with the aim of remaining largely faithful to the message of the original language”. In the third, “they are free adaptations into another language”.3

我关于歌曲语际翻译的研究1侧重于词曲创作在歌曲翻译中的作用。我从做文献综述开始着手。关于歌曲语际翻译的研究,露西尔・德斯布拉什(Lucile Desblache)提出了三种主要形式。2第一种是 “歌词被单独呈现给读者或听众,或者与原曲或音乐文本共同呈现”。第二种是 “歌词以另一种语言演唱,并力求忠实于原语言的词义”。第三种是 “歌词被自由改编成另一种语言”。3

Peter Low categorises song translation into translation, adaptation and replacement text, and proposes that “Adaptation is indeed one way of carrying songs across language borders.”4 Johan Franzon, meanwhile, proposes five choices in song translation.5 The first is to leave them untranslated. The second is “translating the lyrics but not taking the music into account” (e.g. libretto in opera). The third involves “writing new lyrics to the original music with no overt relation to the original lyrics”. The fourth is “translating the lyrics and adapting the music accordingly – sometimes to the extent that a brand-new composition is deemed necessary” (as is often seen in popular, rock and folk music).

彼得・洛(Peter Low)将歌曲翻译分类为翻译、改编和替代文本,并提出 “改编是歌曲跨越语言边界的一种有效方式”。4 约翰・弗兰宗(Johan Franzon)进一步提出了歌曲翻译的五种选择。5 第一种是不翻译歌词,保留原语言。第二种是 “仅翻译词义而不考虑曲调”(如歌剧唱词)。第三种是 “为原曲赋新词,且与原词无明显关联”。第四种是 “在翻译歌词的同时对曲调进行改编 —— 有时甚至需要创作全新曲目”(常见于流行乐、摇滚乐和民谣)。

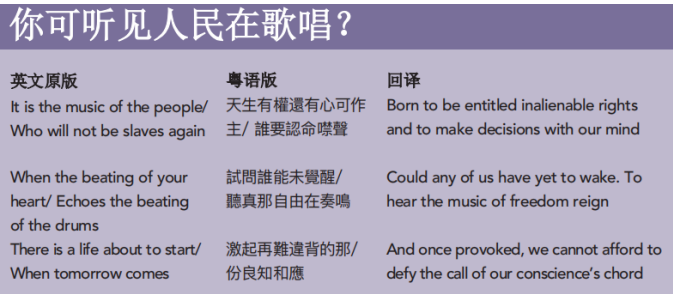

The fifth involves “adapting the translation to the original music”, which is similar to Desblache’s second or third form. A Cantonese version of ‘Do You Hear the People Sing?’ from the musical Les Misérables uses the third method while a Mandarin version uses the fourth with the music unadapted. The lyrics of both versions are adapted to the original music (see below).

第五种是 “将翻译融入原曲中”,这与德斯布拉什(Desblache)提出的第二、第三种形式相似。以《悲惨世界》音乐剧 中‘Do You Hear the People Sing?’为例,其粤语版本采用了第三种选择,而普通话版本则采取了第四种,音乐未做改编。两个版本的歌词都根据原乐进行了改编(见第 12 页的框文)。

It is important to distinguish between song lyrics and song text, though the two are easily confused. Lyrics are ‘singable’ while song text may not be; in other words, song lyrics serve for singing purposes and can be regarded as ‘song text’ or a subcategory of ‘song text’.

区分歌词和歌曲文本具有重要意义,虽然两者很容易混淆。歌词为 “可唱” 之文本,而歌曲文本则不一定具备此特性;换言之,歌词是专为演唱而创作的,可视为歌曲文本或其子类别。

The translation approach will depend on the reason for producing the target text – whether to create song lyrics for the purpose of singing in the target language or to create a written translation without the purpose of singing. In the former, the meaning of the target lyrics will not be the same as that of the source lyrics. The original messages can be reduced, adapted, rewritten or abandoned. Moreover, Desblache states that music has “inspired new forms of translation” in recent decades. This includes localising songs, where the new lyrics vary according to the target culture, audience, language and social milieu.

歌曲文本翻译方法的选择应依据目标文本的用途而定 — 即是为了创作符合目标语言演唱习惯的歌词,还是仅提供书面翻译以便理解原意。对于前者,目标语言中歌词在意义与用词上往往会与原歌词存在差异。原有的词意可能会被简化、改编、重写或舍弃。此外,德斯布拉什(Desblache)还指出,音乐在近几十年来 “激发了新的翻译形式”。其中包括了歌曲的本地化,改编的新歌词会根据目标文化、受众、语言和社会环境而呈现不同风貌。

The purposes of translation

翻译的目的

New lyrics can be localised to reflect social and current affairs. The Cantonese version of ‘Do You Hear the People Sing?’ was first posted on Facebook by the campaign group ‘Occupy Central with Love and Peace’ in May 2014, as discontent was growing in Hong Kong. In light of this societal background, which led to the ‘Umbrella Revolution’ street protests, it has been presumed that the translation was produced for use in the protests. The Cantonese lyrics support this assumption (see table, above).

新歌词可通过本地化反映特定社会语境。例如,粤语版本的 ‘Do You Hear the People Sing?’ 最早由 “占中(Occupy Central with Love and Peace)” 运动小组于 2014 年 5 月在脸书上发布,当时香港民众的不满情绪日益高涨,最终促成了 “雨伞革命”。基于这一社会背景,可以推测该译词是为抗议活动而制作的。粤语版的歌词亦印证了这一假设(见下方的框文)。

A singable target song can be regarded as a localised song if the majority of the target lyrics bear different meaning and words from the source song lyrics. This is acceptable if the aim is to create new singable lyrics that have no relation to the source lyrics.

若目标歌曲是 “可唱的”,且目标歌词在意义和用词上与原歌词差异较大,则可以视为本地化歌曲。接受这种做法的前提是,翻译目的为创作与原歌词无直接关联的新歌词。

When the purpose is to preserve the meaning without considering singability, 100% must be faithfully translated. This can help target audiences to understand the ideas and messages of the original song. For instance, in opera, singers rarely perform in the target language and libretto is used instead. Back translation or literal translation of lyrics is common among ‘fan translation’ for the same reason. In films or TV series, interlingual subtitling is often used to help viewers understand the dialogue. When a character is singing, or a song plays in the background, the lyrics are also translated but unsingable.

反之,若目的在于保留原意,而不考虑可唱性,翻译必须百分百地忠实于原歌词,从而帮助目标受众理解原歌曲的思想和主旨。例如,在歌剧中,歌者很少用目标语言演唱,而是使用剧本唱词。出于同样的原因,歌词的回译或直译在 “粉丝翻译” 中也很常见。在电影或电视剧中,语际字幕经常被用来帮助观众理解对白。当影视角色在唱歌或背景音乐在播放时,歌词大意也会被翻译成目标语言,但通常难以完全契合原曲旋律。

The assessment of categories of song translation should be carried out using specific criteria. Where Low, Franzon and Desblache refer to a ‘majority’ of text being of a certain type (e.g. differing in meaning to the original), that majority should be defined with a scale when target and source lyrics are compared.

评估歌曲翻译的类别应参照洛、弗兰宗和德斯布拉什的观点,即当译后歌词大部分内容与原词意义存在差异时,应予以明确界定。

Accordingly, I propose that a song text can be regarded as ‘translated’ if the singable target lyrics retain 91% or more of the original meaning of the source lyrics. It can be regarded as ‘adapted’ if the scale decreases to 51-90%, and as ‘rewritten’ when the percentage reaches 11-50%. Finally, it can be considered ‘brand new’ when it retains 10% or less of the meaning.

基于此,我建议:若可唱目标歌词保留原意达 91% 或以上,则可归类为 “翻译”;若原意保留比例介于 51% 至 90%,则为 “改编”;当比例介于 11% 至 50% 时,则可视为 “重写”;而当保留意义少于或等于 10% 时,则可认定为 “全新创作”。

Producing singable lyrics

创作可唱歌词

To produce singable target lyrics, Low suggests translators should pay attention to vowels in order to produce songs that rhyme.6 Thus, songwriting can play a pivotal role in song translation, taking song structure, melody, rhythm and rhyme into account.

在创作可唱歌词方面,彼得・洛建议翻译者应注意元音处理,以便创作出押韵的歌词。6 由此可见,作词在歌曲翻译中发挥关键作用,须兼顾歌曲结构、旋律、节奏和韵律。

Songwriters can adjust the order of the words in the target lyrics to adapt the syllables to the music, so that the lyrics can be both singable by singers and listenable to by target audiences. This can help develop lyrics that are not only “possible to sing”, but also “suitable for singing” and “easy to sing”, says Franzon.7 New singable lyrics can be either faithful or not to the original meaning.

词曲作者可以调整译后歌词中的词语顺序,使音节与音乐相契合,从而既保证歌词的可唱性,又便于听众理解。弗兰宗认为,这有助于创作出既 “可唱”,又 “适合唱”,并且 “容易唱” 的歌词。7 而这些新歌词既可能忠实于原意,也可能有所偏离。

Furthermore, when songwriting, music theory and practice are applied to song translation, dubbing or covers, the target lyrics imbue a high aesthetic appreciation of music. For instance, 流れ星 (‘Meteor’),8 a Japanese version of the Mandarin pop song 小幸運 (‘Little Happiness’), sung by Marina Araki, uses new lyrics. They bear little resemblance to the original lyrics, but carry the same sense of a relationship ending and similar emotions of loss, confusion and sadness.

此外,当把音乐理论和实践应用于歌曲翻译、配音或翻唱时,可使目标歌词展现更高的音乐审美价值。例如,由 Marina Araki 演唱的中文流行歌曲《小幸运》的日文版《流星》,8 歌词虽然与原歌词相去甚远,但传达了相同的情感 —— 对于感情终结的惆怅以及相似的失落、困惑和悲伤情感。

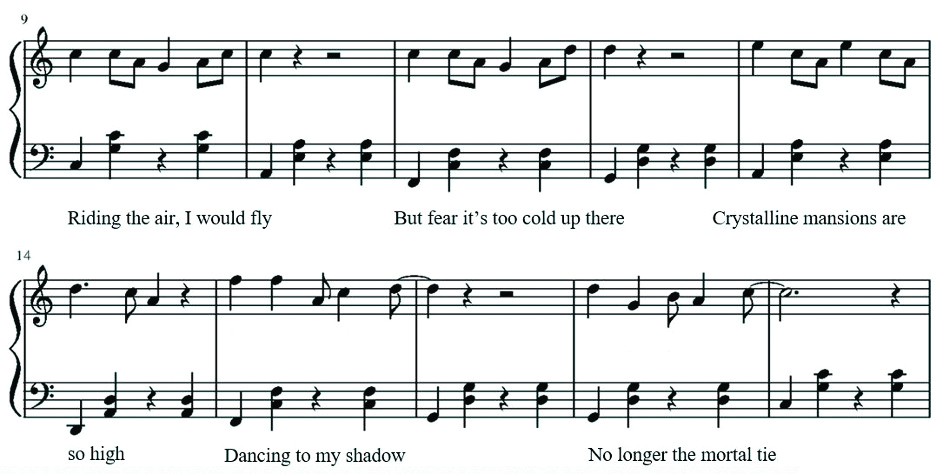

My English version of the Mandarin song 但願人長久 (‘Prelude to Water Melody’) composed by Vincent Liang has singable lyrics in English. I paid attention not only to rhyme and vowel sounds, but also to musical elements, including song structure and poeticity, to improve singability. For instance, I adjusted the word order from 唯恐瓊樓玉宇, 高處不勝寒 (lit. ‘But fear that the crystalline mansions are so high and too cold there’) to ‘But fear it is too cold up there/ Crystalline mansions are so high’. In this way, the lyrics are adapted to the music:

本人创作的英文版《但愿人长久》(《水调歌头》),由梁弘志作曲,其英文歌词具备较高可唱性。在翻译过程中,我不仅注重押韵和元音的和谐,还特别考虑了韵律元素,包括歌曲结构和诗意的呈现,以提升歌词的可唱性。例如,我将词序从 “唯恐琼楼玉宇,高处不胜寒”(字面意思为 “但担心那晶莹的楼阁太高,那里太冷”)调整为 “但担心那里太冷 / 晶莹的楼阁如此高耸”(见上图)。通过这种方式,使歌词更契合旋律要求。

In verse 1, I adapted the number of syllables to the music. For instance, I omitted ‘[I] do not know that’ from the lyric 不知天上宮闕, 今夕是何年 (lit. ‘[I] do not know that in the celestial palace, which year it is on this day?’),9 because audiences can understand it is a question without that phrase. I also ensured the lines rhyme: ‘In the celestial palace up so high/ What day tonight goes by?’ Previous poetic translations did not aim at singability, though they preserved the meaning and main idea of the original poem.10

在第一段歌词中,我根据音乐调整了音节数量。例如,我在 “不知天上宫阙,今夕是何年”(字面意思为 “不知道在天上的宫殿里,今天是哪一年”)中省略了 “不知”,9 因为即使没有这个词语,听众也能理解这是一个疑问句。我还确保了句子的押韵:In the celestial palace up so high/What day tonight goes by? 以往的诗歌翻译虽然保留了原诗的意境和主旨,但并未以可唱性为目标。10

Singability, understandability and listenability should be assessed through assessment criteria that help to identify and categorise target lyrics. This will help a translator, songwriter or singer better understand approaches to song translation and select appropriate methods. Thus, to produce singable songs in a language other than the one in which the source was produced, it is important to take musical analysis and performing arts into account.

综上所述,基于特定标准对可唱性、可理解性和可听性的衡量,有助于识别和分类译后歌词,为译者、词曲作者及演唱者深入理解歌曲翻译方法提供参考,并有助于选择适宜的翻译策略。因此,在以另一种语言创作可唱歌曲时,综合考虑音乐分析和表演技术是至关重要的。

Notes

1 Hsu, G (2024) ‘Music and Translation – A Study of “Singability” of Chinese Versions of the English Song “Do You Hear the People Sing” in the Musical “Les Misérables”’; and ‘Interpreting and Translating Music from Classical Chinese Poetry into Modern English Song – A Study Case of SU Shih’s “Prelude to Water Melody”‘. Unpublished research papers

2 Desblache, L (2018) ‘Music Translation’. In Washbourne, K and Van Wyke, B, The Routledge Handbook of Literary Translation, Routledge

3 Desblache, L (2018) ‘Translation of Music’. In Chan, S, An Encyclopedia of Practical Translation and Interpreting, Hong Kong: The Chinese University of Hong Kong Press, 297-324

4 Low, P (2013) ‘When Songs Cross Language Borders’. In The Translator, 19,2, 229-44

5 Franzon, J (2008) ‘Choices in Song Translation’. In The Translator, 14,2, 373-99

6 Low, P (2008) ‘Translating Songs That Rhyme’. In Perspectives, 16,1-2, 1-20

7 Franzon, J (2015) ‘Three Dimensions of Singability. An approach to subtitled and sung translations’. In Proto, T, Canettieri, P and Valenti, G, Text and Tune. On the association of music and lyrics in sung verse, Bern: Peter Lang, 333-46

8 林さん(2017) ‘流れ星 - 荒木毬菜’; jpmarumaru.com/tw/JPSongPlay-6484.html

9 何年 literally means ‘which year’, but because Chinese is paratactic, it is generic and could also mean ‘which festival/day/moment/night’.

10 Xie, K (2016) ‘四位英文大師翻譯蘇軾的"水調歌頭.明月幾時有’; https://cutt.ly/Nee6e4KI

注释

1 Hsu, G (2024)《音乐与翻译 —— 关于音乐剧〈悲惨世界〉中英文歌曲〈Do You Hear the People Sing?〉中文版本 “可唱性” 的研究》以及《将古典汉语诗歌翻译为现代英文歌曲 —— 以苏轼〈水调歌头〉为例的研究》。未发表的研究论文。

2 Desblache, L (2018)《音乐翻译》。载于 Washbourne, K 和 Van Wyke, B 编,《文学翻译的 Routledge 手册》,Routledge 出版社。

3 Desblache, L.(2018).《音乐翻译》。载于陈善伟编,《实用翻译与口译百科全书》(第 297 - 324 页)。香港:香港中文大学出版社。

4 Low, P.(2013).《当歌曲跨越语言边界》。《译者》,19 (2), 229 - 244。

5 Franzon, J.(2008).《歌曲翻译中的选择》。《译者》,14 (2), 373 - 399。

6 Low, P.(2008).《翻译押韵的歌曲》。《视角:翻译理论与实践研究》,16 (1 - 2), 1 - 20。

7 Franzon, J (2015)《可唱性的三个维度:字幕与演唱翻译的一种方法》。载于 Proto, T, Canettieri, P 和 Valenti, G 编,《文本与曲调:歌曲中音乐与歌词的结合》,伯尔尼:Peter Lang 出版社,333 - 46。

8 林さん (2017)《流れ星 - 荒木毬菜》;jpmarumaru.com/tw/JPSongPlay - 6484.html。

9 “何年” 字面意思是 “哪一年”,但由于汉语是意合语言,它也可以是泛指,意为 “哪个节日 / 日子 / 时刻 / 夜晚”。

10 Xie, K (2016)《四位英文大师翻译苏轼的〈水调歌头・明月几时 有〉;https://cutt.ly/Nee6e4KI。

Gene Hsu (legal name Jingqiao Xu) focuses on music and translation/languages in her interdisciplinary and intercultural research, drawing attention to song analysis, covers and songwriting when studying song translation. She has presented her papers at global academic conferences.

This article is reproduced from the Summer 2024 issue of The Linguist.

Read the article in Chinese here.

You can also read other articles in this series translated into Chinese:

More

The Chartered Institute of Linguists (CIOL), Incorporated by Royal Charter, Registered in England and Wales Number RC 000808 and the IoL Educational Trust (IoLET), trading as CIOL Qualifications, Company limited by Guarantee, Registered in England and Wales Number 04297497 and Registered Charity Number 1090263. CIOL is a not-for-profit organisation.